What is Tachycardia

A heart rate in adults that is greater than 100 beats per minute is technically defined as tachycardia. Many things can cause tachycardia—fever, shock, medications, stress, metabolic dysfunction, hypoxemia, etc.

Perfusion problems may develop when the heart beats too fast and the ventricles are not able to fully fill with blood. This is called the ejection fraction compromise, due to the lack of pre-load before the heart fully contracts. This can cause a decrease in cardiac output, poor perfusion, and hemodynamic instability.

Signs and Symptoms of Tachycardia

The patient’s signs and symptoms should be quickly assessed to see if the symptoms are a result of the tachycardia. A patient with a heart rate of 100 to 150 bpm rarely has symptoms related to the tachycardia. Symptoms in this range are typically a result of another medical issue. But the higher the heart rate, the more likely tachycardia is the culprit of the patient’s symptoms. A thorough primary and secondary survey will help to properly assess the patient’s condition.

Tachycardia Treatment

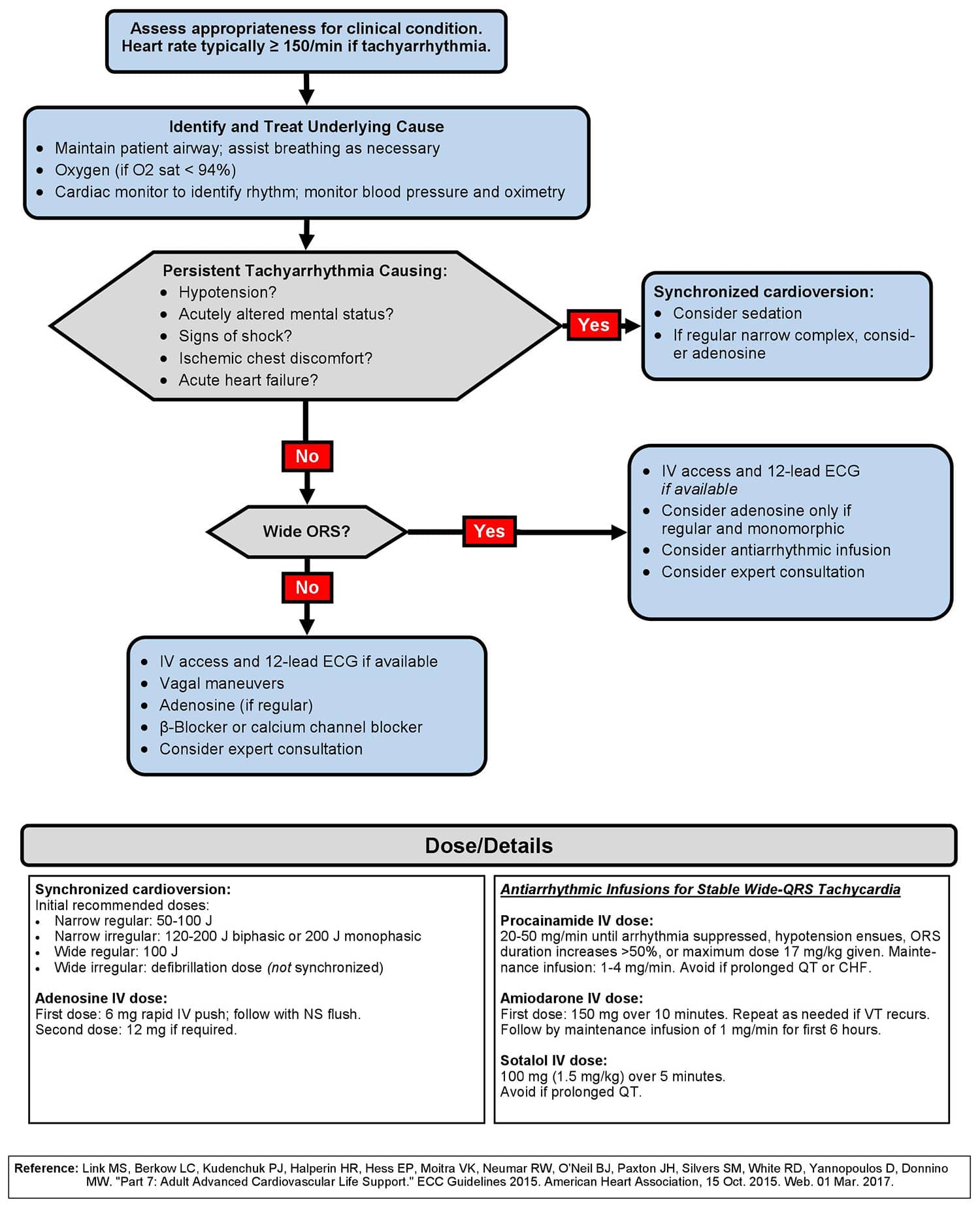

When there is a patient with tachycardia, the first step is to identify whether or not the patient is stable. A stable patient usually does not have any serious signs or symptoms from the increased heart rate. In other words, there is no altered mental status, no chest pain, no hypotension, or any other signs of shock.

For a stable patient, the ACLS team should:

- Check patient vitals

- Monitor oxygen saturation

- Give oxygen as needed

- Get an ECG or 12 lead

- Identify the heart rhythm

- Start an IV

If the patient is unstable, synchronized cardioversion should be done immediately. If time permits and the patient is conscious, sedation may be considered to help with the discomfort from the electrical therapy. But if time does not permit, one may need to defibrillate regardless of sedation.

If a patient does not have a pulse, the rhythm should be treated as if it were ventricular fibrillation, following the pulseless arrest algorithm.

The first step to identifying a tachycardic heart rhythm is to determine if the QRS complex is wide or narrow. A wide QRS complex is .12 seconds or greater, and a narrow QRS is less than .12 seconds. Narrow complex tachycardias typically originate above the ventricles, while wide complex tachycardias typically originate in the ventricles and have a higher risk of deteriorating into cardiac arrest.

For a patient with a regular narrow-complex stable tachycardia, vagal maneuvers should be attempted first. If that does not work, adenosine can be given at 6 mg rapid IV push. If the patient does not convert and remains stable, a second dose of adenosine can be given at 12 mg rapid IV push. After receiving adenosine, patients may feel breathless or feel as if their heart is skipping a beat. This will pass quickly, and they will return to feeling normal.

For a stable patient with an ECG rhythm that shows an irregular narrow-complex QRS tachycardia, it is probably atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or multifocal atrial tachycardia. This would require expert consultation for treatment.

An expert consultation is also required for a stable patient that has regular or irregular wide-complex QRS tachycardia. Often, antiarrhythmics, such as procainamide or amiodarone, are used to treat this. However, the management and treatment of wide complex stable tachycardias requires advanced knowledge of ECG rhythm interpretation and antiarrhythmic therapy.

Adult Tachycardia with a Pulse Algorithm